By Sharon Mizota

As the Trump administration brutally dismantles our social safety net and destroys the pillars of our democracy (to say nothing of human rights), it may appear out of touch to celebrate arts criticism. How can we champion sharing thoughts about art when our neighbors are abducted off the street or don’t know where their next meal is coming from? It might seem oblivious to argue about a painting, a song, or a TV show while the government tramples our civil rights in the next room. Arts criticism has always seemed like a luxury—or a heady exercise in elitism—but this latest crisis reminds me it’s a formative ground for vibrant, independent expression, a civic skill we need to nurture.

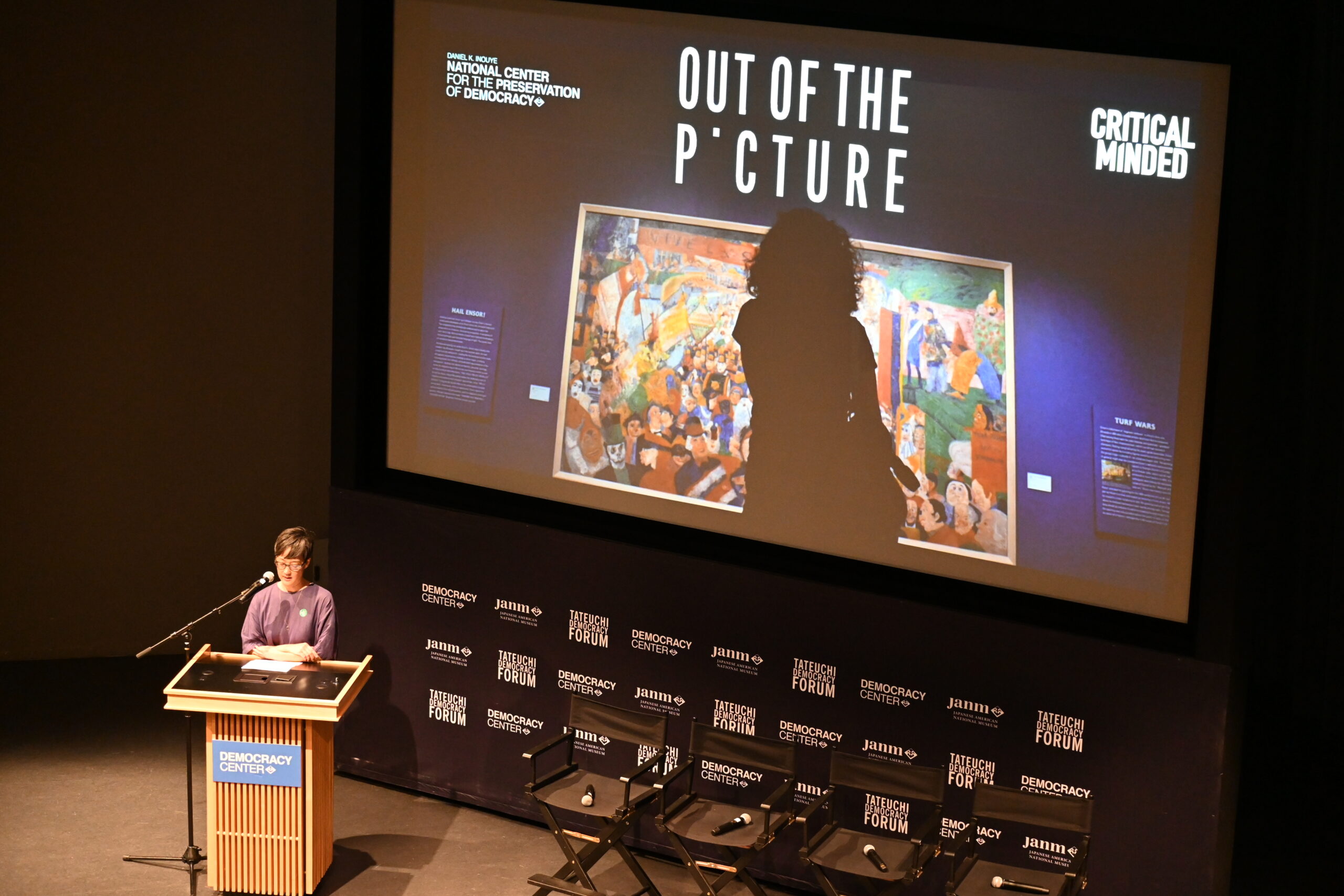

This September, we gathered at the Democracy Center to celebrate this skill. The evening featured a screening of Out of the Picture, an incisive documentary about US art critics. It was followed by a panel discussion with four Los Angeles arts critics about how to better support diverse voices and inspire people to participate. We also celebrated the 2025 recipients of the Democracy Center’s Irene Yamamoto Arts Writers Fellowship, and the Rabkin Prize, as well as the publication of Topdogs and Underdogs: Critics of Color and the Theatrical Landscape, the first report to focus on experiences and challenges faced by critics of color. The event was well-attended and a rare opportunity for critics and journalists to gather and celebrate our craft. It was also a rebuke to the ICE raids happening outside, on the same ground where Japanese Americans were unjustly rounded up and shipped off to concentration camps during World War II.

The gathering was especially important as the very existence of critical voices and freedom of speech are under threat: we continue to weather the economic collapse of journalism while the government cuts longstanding arts and culture funding, launches spurious attacks on news media, and suppresses and erases facts and histories that don’t conform to its white nationalist world view.

I underscore these attacks on journalism because whether we avow it or not, arts critics are a species of journalist. Reporters gather and present facts from the outside world; critics report on what happens inside us. By sharing our responses to art, we start a conversation. In the process, our interior thoughts, feelings, and judgments become public discourse and historical record: in some cases, a work of criticism is the only evidence that a performance or exhibition took place. Arts criticism gives voice to what happens when we reach out; it’s proof of our shared humanity.

It also teaches us how to be critical. Growing up in the 1980s, I first encountered criticism through the San Francisco Chronicle’s capsule movie reviews. Each review was accompanied by a tiny illustration of a man sitting in a chair. In accordance with whether the film was great, good, or bad, he jumped up clapping, sat upright, or slept. My favorites were those where the chair was completely empty: the worst. These negative reviews were often funny, feisty, entertaining. I didn’t see many of the films, but I enjoyed the opinions; I enjoyed their opinionated-ness. They were tiny slices of someone else’s world, which enlarged mine. They made me feel like I could have an opinion too.

Nowadays, public discourse is filled with opinions, but algorithmically driven social media only serves us content that reinforces our existing outrage or love, with little in between. Online spaces—where it feels like most interactions take place—are echo chambers where we don’t learn how to deal with difference or conflict, except to block, cancel, and doxx. We’re drowning in criticism, but we have lost sight of what it’s for: connecting.

Arts critics can show us how to engage with more generosity. Some of my favorites, like Aruna D’Souza, Carolina Miranda, and Seph Rodney, often start out talking about art but end up showing us ourselves, how we relate to one another and the forces that structure our lives. Few are better at this than Hanif Abdurraqib. His essay, “On Going Home as Performance,”[1] explores the complex mourning rituals for Michael Jackson and Aretha Franklin, juxtaposing them with an orca mother clinging to her dead calf, and the last, stubborn leaves to fall in winter. Reading it, I feel how holding on is both grief and celebration, nowhere more so than in the face of oppression. I become part of a story larger than myself.

Looking inward in order to turn towards the world is a form of politics; it is thinking and feeling in public, arguing, advocating, maybe convincing or seeding something new. You may not care what I have to say about a painting—who cares about painting when the world is burning?—but that painting can be an occasion to talk about more consequential things, a buffer between me and you where we can disagree. For me, arts criticism has been a training ground for knowing my own mind, figuring out how to meaningfully share it with others, and considering different views. It seems like a useful tool for rebuilding a democracy.

[1] Hanif Abdurraqib, A Little Devil In America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance (Random House, 2021), 23-35.

Clockwise from left: Carolina A. Miranda, Steven Vargas, the Out of the Picture documentary, the 2025 Irene Yamamoto Arts Writers Fellows, and Tre’vell Anderson. Photos by Sherrill Ingalls.

About the Author

Sharon Mizota is an art critic and archivist who has written for the Los Angeles Times, Hyperallergic, Artforum, X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly, ARTNews, and other publications. She is a recipient of an Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers’ Grant and a coauthor of the award-winning book, Fresh Talk/Daring Gazes: Conversations on Asian American Art. She has served as a mentor in the International Art Critics Association Art Writing Workshop, and is the founder of the Irene Yamamoto Arts Writers Fellowship, which provides financial support for emerging arts writers. Sharon studied visual art at the University of California, Berkeley, received her MFA from Rutgers University and her MLIS from San Jose State University. She lives on unceded Tongva and Chumash land in Southern California.

This is a Guest Blogger contribution to the Democracy Center blog. The views and opinions expressed by blog contributors are not necessarily those of the Democracy Center nor the Japanese American National Museum (JANM). The Democracy Center makes every effort to verify the information provided but makes no representation as to the accuracy or completeness of that information. The Democracy Center is not liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The Democracy Center does not accept unsolicited blog posts or proposals. These terms and conditions of use are subject to change at any time and without notice. Please direct any concerns to DemocracyCenter@janm.org. For more information on JANM’s terms of service, please visit: janm.org/about/terms-of-service